PODCAST:

TRANSCRIPT:

Many years ago I asked my former Ph.D. advisor why he chose to write a particular book that he had published some years back. His name was Gary Madison and the book in question was on political philosophy. Gary’s field in those days was phenomenology and hermeneutics. His answer surprised me and it has always stayed with me. He said, I realized I didn’t know anything about political philosophy, so I decided to write a book about it. I decided then that that’s an attitude I would adopt, and it’s not exactly the norm in the academic world.

There’s an interesting dilemma that characterizes the academic profession today, in philosophy and more or less every discipline. On one hand, the trend we’ve seen for over a century now has seen academics in every field becoming increasingly specialized. A professional philosopher today, for instance, isn’t a generalist of the kind that was common a century or more ago but an expert in maybe one or two of the many subdisciplines our field contains. More than that, one is typically an expert not in the entirety of that subdiscipline but in a particular set of issues within it and spends a good part of one’s career and maybe all of it working on those issues. Of philosophy’s many other subdisciplines one usually knows little, essentially whatever one learned in one’s student days and then only here and there through the course of a career. On the other hand, we often hear university administrators, granting bodies, and others urging academics to undertake more interdisciplinary forms of research, or if not interdisciplinary then at least intersubdisciplinary or otherwise to look up from the usually small patch of ground one has been plowing and replowing and to bring this into conversation with some larger and maybe global perspective. Interdisciplinarity has become a trend, and one that is likely for the better, at least in some ways, but there’s a difficulty here that pertains to how we prepare graduate students to enter the profession.

Anyone who has spent much time in a philosophy department in the last thirty years or so knows that there are very few jobs in this field and in the humanities generally. Hiring committees are continually faced with massive applicant pools even at institutions considered less reputable and less desirable places to work. The job market isn’t likely to get any better anytime soon, in just about any country one cares to name. To get the tenure-track job that every young academic wants, they need to hit the job market with the necessary credentials which importantly include what’s called an area of specialization or AOS. Job ads specify this and often, as a secondary matter, a secondary area of competence as well, meaning essentially one in which one would be comfortable teaching an undergraduate course.

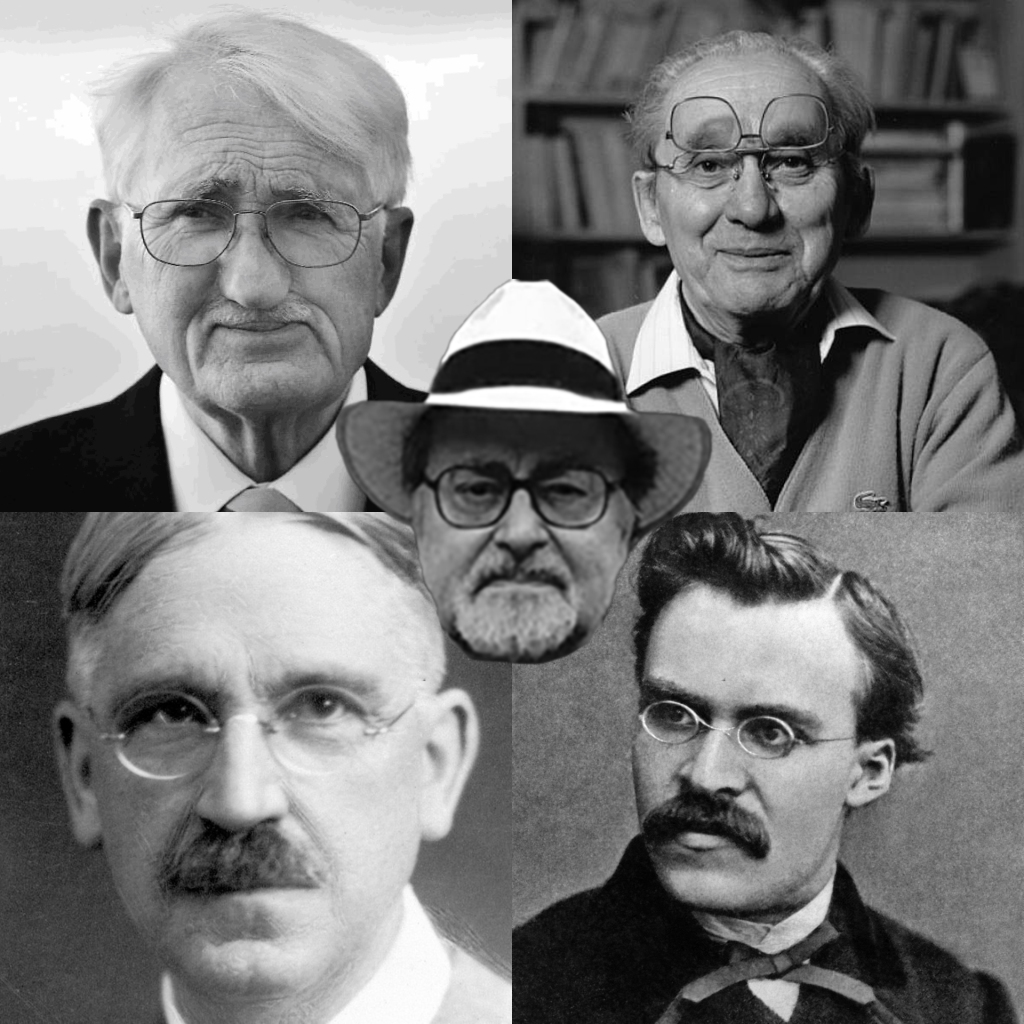

Let’s go back in time somewhat and look at a few of the more important philosophers of the last century or more. Think of Nietzsche, for example, who was writing in the 1870s and 80s. What was his AOS? He didn’t have one. Was his work interdisciplinary? Indeed it was. He wrote quite a few books on a wide range of topics: ethics, aesthetics, metaphysics, theory of knowledge, philosophy of science, philosophy of religion, and various others too. What about John Dewey, moving into the early and middle part of the twentieth century? We can say the same about him, except that he wrote even more books on an even wider range of subjects. Let’s think of a couple of more recent names. Paul Ricoeur was one of the preeminent French philosophers of the second half of the last century. He too wrote a large number of books and essays on many topics: aesthetics, philosophy of time and history, ethics, hermeneutics, existentialism, and a few others. Among the Ph.D. students he supervised was the above-mentioned Gary Madison, who also went on to write a number of books in about the same number of fields. One of the best known living philosophers is Jürgen Habermas, who has made major contributions to ethics and political theory, philosophy of law, the theory of rationality, and some others. Like these other writers, he has often been read not only by philosophers but by academics in several cognate disciplines. Again, what is his AOS? Maybe critical theory, but that term is a very large umbrella.

The great majority of academics today, including many very successful ones, aren’t doing what they did. They are spending their whole career as specialists, for one reason or another. One might wonder why this is. You might think that a philosopher, unlike say a physicist or a biologist, is a free spirit, someone who has both the curiosity and the freedom to break out of their AOS and to venture somewhere else from time to time. Why don’t more of them do this? Is it something in the nature of knowledge itself, a consequence of professionalization, or something else? In the natural sciences the advance of knowledge seems genuinely to require a narrow focus on the part of individual researchers, but is the same true of philosophers? I don’t think so. If it were then the writers I have just mentioned could not have pulled off what they did. A more likely explanation for the narrowing of focus and perspective that is the norm today lies not in the nature of knowledge but in the realities of the profession as it presently exists. A member of this, like any, profession finds oneself first in a job market and then in an institutional setting that includes a system of incentives and disincentives, norms governing promotion, research funding, and so on, which typically has a good deal of influence on what individual academics do. What tends to get rewarded is precisely the specialist, one who, for example, is able to say in a grant proposal that they are ideally suited to carry out a particular line of research for the reason that they have done something very much like this before and are continuing a long-term research project which may in the end consume a career. What would happen if a philosopher were to apply today for a grant to work in a field that is new to them and points out that he or she is endeavoring to be interdisciplinary or intersubdisciplinary? They’re likely to be turned down.

It has long been my opinion that philosophers, or a good majority of us, don’t need research grants, which is why I never apply for them—nor did Gary. We don’t have labs or expensive equipment to buy, and I wouldn’t know what to do with a research assistant. I’ve never had one and don’t want one. My opinion, however, is very much in the minority and academics in every field regularly apply for grants and are also strongly encouraged to do so by university administrators, sometimes the very ones who proclaim the need for greater interdisciplinarity. It has long been my view as well that it’s on the border between disciplines, schools of thought, and whole traditions that much of the more innovative philosophical work tends to be done, precisely by nonspecialists or individuals, at any rate, who prefer to move around some and to follow their noses regardless of whether they’ll be rewarded for it in the ways the profession does.

I don’t know whether the philosophers I have mentioned were responding to incentives and disincentives or pursuing the rewards that this profession sometimes hands out, but I very much doubt it. I know that Gary wasn’t. Nietzsche wasn’t a professor at all, or not for long, and not when he was writing his most important works. The other three were, but in each of their cases what it seems to me they were doing was striving for a more comprehensive view of the human condition than what any specialist could pursue. I hope that more philosophers of their sort come along, and the reason I believe they will not is that the kind of broad-mindedness that interdisciplinarity calls for is being selected against by the very profession and institution in which philosophers now find ourselves. If the problem of overspecialization is ever to be solved, my guess is that it will be solved not by tenured professors in our more reputable universities but by some in the large and growing number of independent scholars who whether by choice or necessity make their living either on the margins of the universities or wholly outside of them.

|

|

#nietzsche #paulricoeur #jurgenhabermas #johndewey #philosophy #phenomenology #academia #humanities

Leave a comment